At SetPT, we see many patients with shoulder injuries. A crucial component to rehabing shoulder issues is knowledge of the mechanics and structure of the shoulder, which is a very complex joint. In this five part series, we'll review the structure and function of the shoulder complex, talk about the most common shoulder injuries, including rotator cuff syndrome, frozen shoulder, and instability, and finish with interventions and common rehabilitation guidelines.

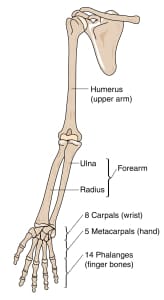

To understand how to treat the shoulder, we must consider the biomechanics of the entire shoulder complex. The shoulder complex consists of the humeral head, the scapula, the sternum, and the clavicle.

Primary shoulder joints

- Glenohumeral joint: where the humeral head meets the glenoid. Ball and socket joint, but more like a golf ball on a golf tee.

- Acromioclavicular joint: where the collarbone meets the acromion, a bony protrusion from the shoulder blade.

- Sternoclavicular joint: where the collarbone meets the sternum.

- Scapulothoracic joint: not a traditional joint, but the shoulder blade on the thorax (ribcage).

Because the shoulder has many degrees of movement, meaning it can move in multiple directions in multiple planes, it lacks stability found at joints that only have two planes of movement (the elbow, for example).

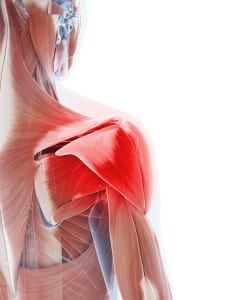

The shoulder complex has many muscular attachments, but most of the stability is provided by tough, fibrous ligaments at each joint. The most important muscular attachments to the shoulder complex is the rotator cuff, which is a group of four muscles that functions to dynamically to maintain glenohumeral stability.

Muscles of the rotator cuff

- Infraspinatus: lies on top of the shoulder blade. This muscle helps to externally rotate the shoulder.

- Supraspinatus: found on top of shoulder, tendon runs beneath the acromioclavicular joint. This muscle participates in abduction.

- Subscapularis: beneath the shoulder blade, "sandwiched" between the shoulder blade and rib cage. The subscapularis is the main internal rotator of the shoulder and is the largest and strongest rotator cuff muscle.

- Teres minor: found very close to the infraspinatus, in the back of the armpit. This small muscle helps to externally rotate the shoulder when it is in 90 degrees of abduction.

It is crucial that the four joints, their ligaments, the rotator cuff, and all of the muscles that attach to the shoulder function together to produce fully, functional movement. Deficiencies in any of these structures can lead to shoulder problems. In part 2, we'll explore one of those problems: rotator cuff dysfunctions and shoulder impingement.